Electricity supply

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Most buildings [1] in the UK are connected to a world class, albeit ageing, electricity generation and supply network that has benefitted from immense investment over the years.

In 1925 Lord Weir was asked by the UK Government to solve the issue of a fragmented electricity grid that up until then consisted of a myriad of independent producers all with local networks using different voltages and frequencies.

In 1926, the Electricity Supply Act [2] created the Central Electricity Board that oversaw the development of the UK’s first nationwide AC grid in 1933. Since its introduction the grid has been founded on large scale centralised AC generation primarily based on fossil fuels with the introduction of nuclear electricity in the last sixty years.

Power stations are normally located away from centres of population where fossil fuels are abundant or good transport links exist. Many of these locations are well away from the towns and cities where the electricity is used and hence there is a need for electricity transmission and distribution. To do this efficiently the voltage at which electricity is generated is stepped up for efficient transmission and distribution and then stepped back down for safe usage.

At the time of the grid being established this could only be achieved by the use of linear transformers and these only work on AC [3]. As a result AC grids now dominate throughout the world [4].

[edit] The electricity supply network

The UK’s electricity transmission network is based on a 400 kV AC super grid and a 275 kV transmission network. The local distribution network steps this down through a number of stages from 132 kV to 11 kV although some big industrial users will be supplied with 33 kV or higher. The voltage is then reduced further to 415 V three-phase for small/medium sized commercial and industrial users and finally it is supplied to domestic dwellings at 230 V single- phase (the voltage between one of the three-phases and neutral).

Conversion is by way of linear transformers but unlike some of their smaller counterparts the ones used in the supply of electricity can be extremely efficient, in the region of 99.8 per cent [5], however reactive loads and their non-zero imaginary impedance can reduce this figure under normal operating conditions.

Since de-regulation of the electricity sector the supply network, from generation through to the consumer, is managed by four separate organisations that fulfil very different functions [6]:

- Generators - responsible for producing the electricity.

- Suppliers - responsible for supply and selling electricity to consumers.

- Transmission network - responsible for the transmission of electricity across the country.

- Distributors - those who own and operate the local distribution network from the national transmission network to homes and businesses.

The national grid transmission network is on average 93 per cent efficient and is one of the most reliable in the world with an operational reliability of 99.99998 per cent [7] although these figures only apply to the main transmission network. Reliability and efficiency figures for the local distribution networks are more difficult to come by due to individual network characteristics and estimated billing.

However, with the introduction of smart meters electricity consumption and availability will become a lot clearer allowing local distribution network performance to be better characterised. Overall the conversion of energy from primary fuel at the power station to usable electricity in the home is only in the region of 35 per cent for coal fired power stations and 45 per cent for the most modern Combined Cycle Gas Turbine (CCGT) power stations [8].

[edit] Decarbonising the grid

Peak demand for electricity across all sectors on an Average Cold Spell (ACS) in Great Britain is approximately 60 GW (2013/14). In 2013/14 approximately 350 TWh of electricity was generated and consumed, the majority of which was produced by burning coal and gas, and by nuclear power stations.

In 2035/36, total electricity generation is expected to be over 365 TWh with a peak demand of 68 GW (National Grid, Gone Green scenario). This will rise still further to approximately 600 TWh/yr by 2050 primarily driven by increased electricity exports and the electrification of transport and domestic heating using heat pumps [9].

Domestic electricity consumption has increased by approximately 40 per cent since 1970 although it peaked in 2005/6 and has fallen slightly to 118 TWh in 2013/14. Under the National Grid Gone Green scenario this is expected to fall further to just over 100 TWh by 2025/26 and then rise to over 125 TWh by 2035/36 [9] (note; see reference [9] for other ‘less green’ scenarios). To achieve these modest growth figures requires the domestic sector to meet challenging energy efficiency targets over the next 20 years.

The UK Government has set challenging targets for carbon dioxide reduction and together with the EU’s Large Combustion Plant Directive [10] and the Industrial Emissions Directive it is having a big impact on the UK’s electricity generation capacity. The UK has committed to a 34 per cent reduction in carbon dioxide emissions by 2020 (over 1990 levels) and an 80 per cent reduction by 2050 and to help meet these targets the national electricity supply will need to be more-or- less decarbonised.

In the short term approximately 20 per cent of the existing power plants (coal and nuclear) are due to close in the next five years. This shortfall calls for over £110 bn of new investment in the next decade [11], [12]. To meet carbon dioxide targets the new capacity will be more intermittent and inflexible as a result of renewable generation (primarily wind) and less flexible as a result of nuclear generation.

Due to the intermittency of renewable electricity generation it has a load factor, the estimated contribution as opposed to the maximum potential, of between 30 and 40 per cent for wind, onshore and offshore respectively, and just over 10 per cent for PV. As a result, renewable generation is driving the need for a near doubling of installed capacity over that of today from 91 GW to over 163 GW in 2035 despite only a slight increase in peak demand assuming energy efficiency targets are met [9].

In the shorter term however, at periods of peak demand the loss of generation capacity will have an impact on the headroom available between supply and demand. The prediction is that in high demand periods supply may only just exceed demand by a few per cent, probably around 4% or less. In the past this has typically been held between 10 and 20% so it represents a significant drop in headroom. As a result, the probability of a large shortfall in electricity requiring the controlled disconnection of consumers increases from around 1 in 47 years in the winter of 2013/14 to 1 in 12 years in 2015/16 or lower if energy efficiency measures don’t materialise.

In terms of security of supply two probabilistic measures are used, Loss of Load Expectation (LOLE) and Expected Energy Unserved (EEU). LOLE estimates for the next few years show that demand may exceed supply for more than the target of 3 hours and that this shortfall may be made up of a number of relatively frequent small events or infrequent larger events.

However, the National Grid power supply background has been developed so as not to exceed the 3-hour LOLE threshold from 2018/19 onwards. Before then, while the shortfall is of concern, system operators have some control over the network by for example, reducing electricity exports or selectively disconnecting industrial users, so there may be little or no significant impact on domestic consumers [13].

In general terms the total energy consumption in the domestic sector has seen a change in makeup over the past 40 years with an increasing use of electricity which is likely to continue in the future. Coal has been substituted by natural gas and as the grid becomes decarbonised natural gas will be slowly displaced by electricity.

This article was created by --BRE. It is taken from The future of electricity in domestic buildings, a review, by Andrew Williams, published in November 2014.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Articles about electricity.

- Alternating current and direct current.

- Ampere.

- BEAMA.

- Coal usage for electricity generation to end by October 2024.

- Consumer electronics.

- Domestic micro-generation.

- Electrical consumption.

- Electrical energy.

- Electrical power.

- Electrical safety.

- Electrical system.

- Energy consumption.

- Energy infrastructure.

- Energy storage.

- Engineering Recommendation G99.

- Feed in tariff.

- Glossary of electrical terms.

- Islanded grid.

- Kilowatt hour.

- London Power Tunnels.

- Mains electricity.

- Making Mission Possible: report on achieving a zero-carbon economy by 2030.

- Microgeneration.

- Natural capital, infrastructure banks and energy system renationalisation.

- Power generation.

- Renewable energy.

- Smart Export Guarantee SEG.

- Smart meter.

- Substation.

- Switchgear.

- The future of electricity in domestic buildings.

- The future of UK power generation.

- Total energy supply.

[edit] References

- [1] Estimates are that approximately 40,000 homes in the UK are not connected to the National Grid

- [2] National Grid (online). Timeline – National Grid 75th Anniversary. Accessed 10 January 2014. www.nationalgrid75.com/timeline.

- [3] Author unknown. Triumph of AC 2. The battle of the currents. Power and Energy Magazine, IEEE Journal Volume 1, Issue 4 (19 December 2003) pp 70-73.

- [4] Yung-li (online). World voltage and plug specifications. Accessed 26 February 2014. http://www.Yung-li.com.tw/en/info/ww_specifications.htm.

- [5] National Grid. Be the Source. Accessed 12 February 2014.

- [6] National Grid (online). What we do in the Electricity Industry. Accessed 10 January 2014.

- [7] National Grid. Innovation funding incentive (transmission) annual report. Accessed 13 January 2014.

- [8] Department of Energy and Climate Change (online). Centralised Electricity Generation –Combined Heat and Power Focus.

- [9] National Grid. UK Future Energy Scenarios, UK gas and electricity transmission 2014.

- [10] European Commission. Large Plants Directive (2001/80/EC). Accessed 9 February 2014.

- [11] National Grid. Factsheet, The Energy Challenge. Accessed 13 February 2014.

- [12] Department of Energy & Climate Change. The Energy Act. Downloaded from http://www.gov.uk. Accessed 15 February 2014.

- [13] ofgem. Electricity Capacity Assessment Report 2014.

Featured articles and news

Call for greater recognition of professional standards

Chartered bodies representing more than 1.5 million individuals have written to the UK Government.

Cutting carbon, cost and risk in estate management

Lessons from Cardiff Met’s “Halve the Half” initiative.

Inspiring the next generation to fulfil an electrified future

Technical Manager at ECA on the importance of engagement between industry and education.

Repairing historic stone and slate roofs

The need for a code of practice and technical advice note.

Environmental compliance; a checklist for 2026

Legislative changes, policy shifts, phased rollouts, and compliance updates to be aware of.

UKCW London to tackle sector’s most pressing issues

AI and skills development, ecology and the environment, policy and planning and more.

Managing building safety risks

Across an existing residential portfolio; a client's perspective.

ECA support for Gate Safe’s Safe School Gates Campaign.

Core construction skills explained

Preparing for a career in construction.

Retrofitting for resilience with the Leicester Resilience Hub

Community-serving facilities, enhanced as support and essential services for climate-related disruptions.

Some of the articles relating to water, here to browse. Any missing?

Recognisable Gothic characters, designed to dramatically spout water away from buildings.

A case study and a warning to would-be developers

Creating four dwellings... after half a century of doing this job, why, oh why, is it so difficult?

Reform of the fire engineering profession

Fire Engineers Advisory Panel: Authoritative Statement, reactions and next steps.

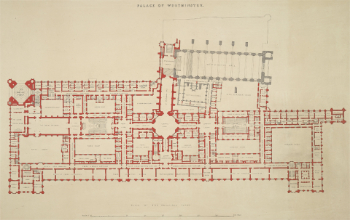

Restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster

A complex project of cultural significance from full decant to EMI, opportunities and a potential a way forward.

Apprenticeships and the responsibility we share

Perspectives from the CIOB President as National Apprentice Week comes to a close.

Comments